A lot has changed about air travel since it went mainstream in the 1930s. On-board smoking, free-flowing booze, and five-star meals have given way to baggage fees, cramped seats, and mystery meat. It ain’t all bad, though — flying is also more safe, affordable and accessible than ever before.

Through all this change, one thing has stayed the same — the software that manages it all.

Booking air travel today isn’t the most pleasant experience, but it used to be a whole lot worse.

Airlines used to employ fleets of operators just to process reservations. They sat around circular tables with scores of index cards — one for each flight — housed on a rotating shelf (a “Lazy Susan”). To book a seat, the operator would have to find the flight’s index card, mark it to indicate the booked seat, and write the flight ticket out by hand. The process would take 90 minutes for each reservation.

This workflow was cumbersome, but did the job. As air travel became more and more popular, though, the reservation system became more and more of a bottleneck. Only 8 operators could fit around a reservations table, so once airlines had many more flights in their fleets and started processing many simultaneous bookings, they began to face serious headwinds.

American Airlines saw this coming, and had started working on solutions. They developed a computerized booking system by 1952, but its workflow remained very manual. Though it allowed many people to look up flight information simultaneously, it still required operators to manually handle ticketing and talk to travel agents over the phone. It was enough to solve their scaling problems in the short-term, but American knew that they were kicking the can down the road.

The trajectory of air travel changed after a chance meeting between the president of American Airlines, and an IBM salesman — on an American flight.

IBM, at the time, was working on a new communication system for the US Air Force. It involved a network of computers that sent and received information using teleprinters, similar to a group of fax machines.

IBM realized that instead of sending messages from radars to interceptor aircraft, they could use the same system to send messages from travel agents to airline ticketing offices. The system would automatically be able to notify agents of available seats, process their bookings, and even print their tickets — all without a human on the other end of the phone.

IBM and American began research on the system almost immediately. 7 years and 40 million dollars later ($350M adjusted for inflation), SABRE (Semi-Automated Business Research Environment*)* took flight. At the time, it was the largest real-time data processing system outside of the US government, and was the first major e-commerce system ever, processing many millions of dollars per day. This was all achieved before the Internet.

SABRE changed the game for American Airlines. It cut the average processing time for a booking down from 90 minutes to a few seconds, giving American a huge competitive advantage. Other airlines had no choice but to do the same, and IBM’s newfound expertise helped them set up their own computer reservation systems (CRS). Airline productivity soared.

After CRS systems became commonplace, travel agents became the airline industry's bottleneck. Because each airline had their own system, it still took a long time for agents to shop around and find the best deals for their clients. So, in 1976, CRS providers launched terminals for travel agents, eliminating the need for inefficient phone calls and letting agents directly access airline reservation databases.

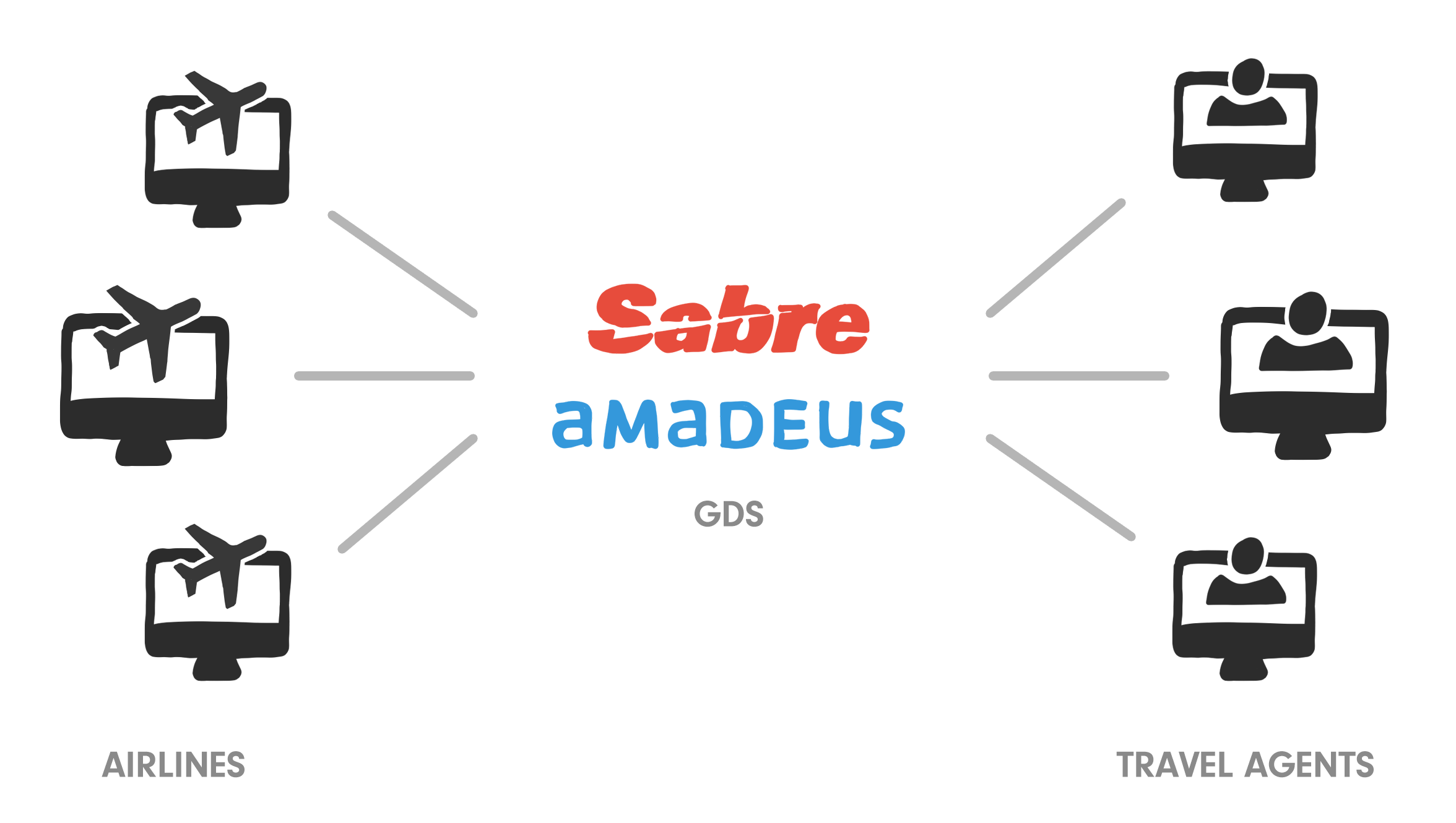

These terminals would only be useful if they let agents search for flights from multiple airlines all together. Thus, the CRS systems started sharing data with one another, leading to the birth of a new industry term — Global Distribution Services (GDS). Agents could use any GDS to book flights on any airline — Sabre (owned by American Airlines at the time) could be used to book United flights, despite the two airlines being competitors. As the middleman, the GDS charged airlines and travel agents a fee for each booking.

Today, the GDS industry is dominated by Sabre and Amadeus, who hold a combined market share of 80%.

How it works

GDS systems were some of the earliest widely-used command-line interfaces (CLIs). They are to the airline industry what Bloomberg Terminal is to finance.

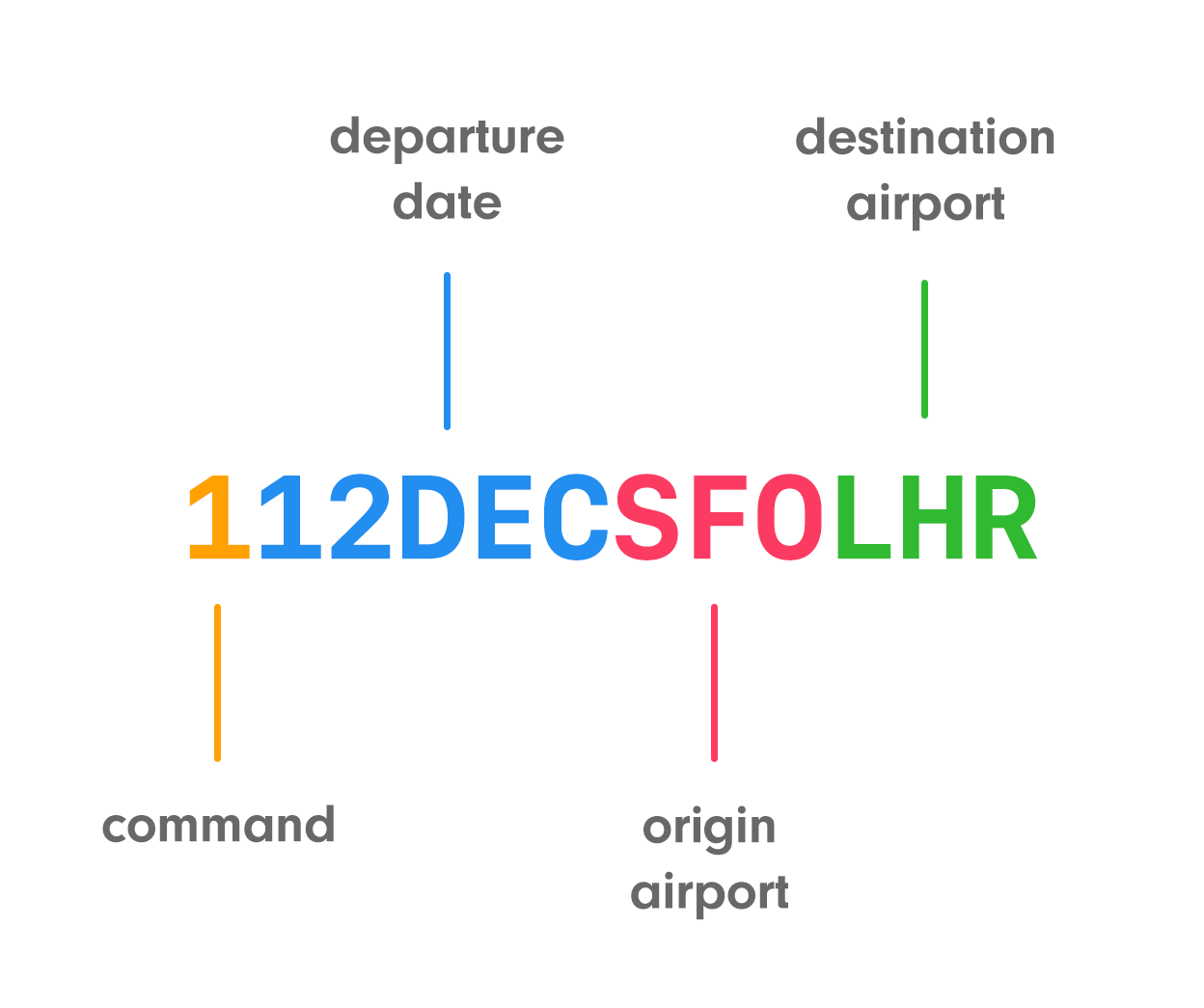

Like any CLI, Sabre’s syntax consists of commands followed by arguments. For example, the 1 command is used to look up available flights. A typical availability lookup might look like this:

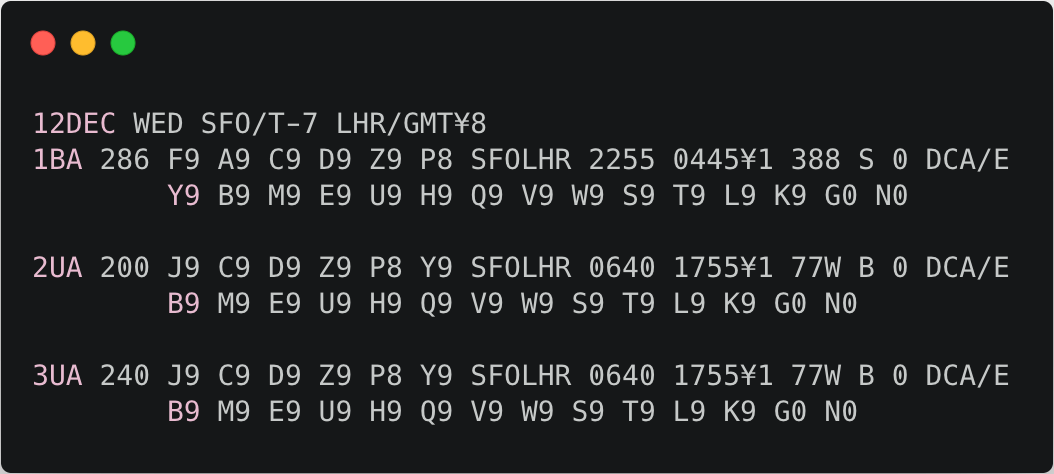

This might output the following:

The first line summarises the search parameters:

12 DEC WED: the departure dateSFO/T-7: the origin airport,SFO, which is in theT(Tango) time zone, which is 7 hours behind Greenwich Mean TimeLHR/GMT¥8: the arrival airport,LHR, which is in theGMTtime zone, which is 8 hours ahead of the origin airport

The remaining sections (2 lines each) show the available flights matching these parameters:

BA 286: the airline code and flight number —BAis a code used by British AirwaysC9 D9 Z9 P8 …: the fare classes and the number of remaining seats on each,C9means there are at least 9 seats in fare classC,P8means there are 8 seats left in classP(more details on fare classes below)SFOLHR: the city pair —SFOis the origin airport andLHRthe arrival airport2255 0445¥1: the departure and arrival time — departing at2255and arriving at04551 day afterwards388: equipment type —388corresponds to Airbus 380-800S: meal type — another command has to be run to decode this into one of the official IATA meal codes, which includeBLML(“Bland Meal”) andCAKE(“Birthday Cake”)0: number of stops —0denotes a non-stop flightDCA/E: the airline’s level of connectivity with Sabre —DCAdenotes direct-connect availability, and/Edenotes that an electronic ticket can be issued

Airline pricing

Two Economy class seats can be close together yet hundreds of dollars apart. Every empty seat at take-off is money left on the table, so airlines price their tickets to maximise revenue from each flight.

Their goal is to charge each customer the most they’d be willing to pay. The family booking their holiday 6 months in advance will be less willing to pay than the businesswoman jetting off to close a deal. If all tickets were priced for holidaymakers, airlines would lose out on money that business travellers would have paid. And if all tickets were priced for business, there would be empty seats that holidaymakers could have filled.

The solution is to have seats at many different price points. Economy, Business, and First are the seat classes that airlines advertise, but each of these is further broken down into multiple fare classes. The fare class is what actually determines a seat’s price. It also determines factors like flexibility (whether you can cancel or change your booking) and air mile ratios (how many air miles you earn for each mile in the air).

A single flight might have 50 different Economy fare classes, with a price difference of over 10x between the highest and lowest. Each fare class has a limited number of seats — if you book early, you might get the $100 fare in the lowest class. But leave it too late and you’ll be stuck with the $1000 fare in the highest — for essentially the same seat.

To maximise revenue, airlines optimise fare class sizes and prices by analysing historical trends. Nowadays, computers do this dynamically in real-time. This is why different Google searches often yield different fares for the same seat on the same flight. Some have hypothesised that flight comparison websites even use browser cookies to change prices based on your search history, but there’s not much hard evidence for this.

Clearly, GDS systems aren’t for the uninitiated. In fact, only travel agencies that have been accredited by the IATA (International Air Transport Authority) can use them, and accreditation is an arduous process riddled with acronyms.

What’s more, travel agents face hefty fines if they make any errors using the GDS. Airlines can issue Agency Debit Memos (ADMs) for any one of 138 reasons. These include credit card chargebacks (typically not the travel agent’s fault), incorrect tax calculations (complex when dealing with different countries), and incorrect refund calculations (some taxes are non-refundable).

Online travel agents (Expedia, Orbitz, etc.) communicate with GDS systems using automated processes, which reduce their ADM fines related to human error. Fraud, though, is a much bigger problem on the Internet, so online agents pay large sums in fines resulting from credit card chargebacks.

Travel agency is already a difficult business, but it’s made harder by the current state of ADMs. The total profit generated by travel agents in 2015 was $2B. The same year, airlines issued $140M in ADM fines. This isn’t a state of affairs that anyone is thrilled about — the IATA is working with airlines and GDSs to better manage and reduce the cost.

It’s worth noting that the most powerful industry software, even today, is command-driven. Finance has Bloomberg Terminal, agriculture has DairyComp, and aviation has GDSs.

Airlines vs GDS

In the early days, GDS systems generated a lot of money for airlines. They provided a whole new distribution channel for flights, giving airlines a way to reach customers without directly marketing to them. Airlines do have to pay a GDS fee, these days around $12 per booking, but it’s historically been worth it.

As ticket prices dropped, though, airlines adapted to find new revenue streams outside of the airfare — add-ons like seat upgrades, priority boarding, and on-board wi-fi.

GDS systems, however, did not adapt with them. Their data format, an archaic standard called EDIFACT, hasn’t changed since the 1960s. In the same way that Amazon doesn’t let 3rd-party sellers customise the checkout process, GDS systems don’t support custom content that airlines want to put out. This costs airlines money, since they can’t sell many flight add-ons (e.g. on-board wi-fi) with tickets booked through the GDS. Airlines have to maintain their own systems to manage this, which is costly both financially and to the customer experience.

This issue has caused much turbulence in the industry. Many airlines are doubling down on their own systems and direct marketing to reduce reliance on the GDS. Lufthansa introduced its own $18 fee for GDS bookings to encourage bookings directly through their site, and budget airline RyanAir will soon be de-listing from Amadeus “after a new commercial agreement could not be reached.”

Old dogs, new tricks

A defragmented airline industry is bad for everyone. It makes it harder for consumers to find the best deals, harder for airlines to distribute their seats, and harder for new innovations to take off.

Thankfully, there might be a solution — XML.

NDC (New Distribution Capability) is a new data standard being promoted by the IATA. Based on XML, it’s much more flexible than its predecessor and supports the features that airlines need. This will not only let them sell flight add-ons with GDS bookings, but also show rich content (text, photos, videos) to customers after they book.

Unlike EDIFACT, XML is an international standard for Internet communication, making it much easier to build new applications on top of. As well as enable existing services between airlines and agents, the IATA hope that NDC will promote much-needed competition in airline distribution products.

It’s always challenging to bring new standards to old industries, but NDC adoption has so far been promising. Sabre and Amadeus (the two biggest GDS players) have both already updated their systems to support NDC, as have many major airlines including United, American, and KLM. The IATA hope for NDC APIs to power 20% of all industry sales by 2020.

Other industries are taking similar steps towards more open and friendly data standards that make innovation easier. PSD2 and Open Banking are initiatives in Europe that require banks and financial institutions to open up their data via APIs, enabling 3rd-parties to develop new finance products. It seems to be working — Europe is leading the way in the “fintech” revolution, with the US struggling to keep up.

Air travel is not an industry without its difficulties. So many airlines have failed over the years that Wikipedia publishes a List of Airline Bankruptcies in the United States.

But the future is looking bright — air travel is growing at twice the rate of GDP. Low-cost airlines are making it ever more accessible, and the industry is already seeing an impressive amount of innovation. With NDS, things are sure to get even better. “This is your captain speaking. Please fasten your seatbelts for take-off.”